I know what you’re thinking: another left-wing nut writing about how tuition fees are too high (no offence intended, fellow left-leaners). Actually, I have serious reservations about writing this article. This is just the next in a series of pieces written by professors and students on tuition fees over the last 10 years – many of which seem to have unfortunately fallen on deaf ears. And I’m not really naïve enough to believe this article will have an immediate impact but if I help start an informed debate, I think it’ll be worth it.

Like many students, before I did the research for this article, I was of the opinion that our high tuition is probably justified. After all, UofT is consistently ranked the top law school in Canada and our entrance stats are essentially equivalent to UC Berkley’s law school, which is ranked seventh in the US and has a yearly tuition of $50,000. We’re getting a deal then, aren’t we? We pay almost half that! That is one way to look at it but I would argue a better way is to see if we actually need to pay half in order to be the Canadian equivalent of UC Berkley.

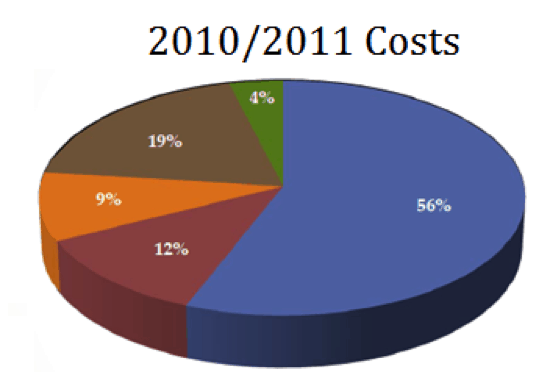

So, how does the school spend our tuition?

Faculty Salaries & Research Support = $10,931,957 (56%)

Student Services & Academic Program Support = $4,156,502 (19%)

Library = $2,288,294 (12%)

Other (Admin, Plant) = $2,038,144 (9%)

Alumni, Development & External Relations = $849,296 (4%)

The first thing you’ll notice is that faculty salaries and research support make up most of the spending. I think that makes sense to most people. Faculty salaries have made up more than 50% of our spending for a little while – at least until 2004 (the oldest year I could get data on). However, while the percentage of the pie spent on faculty has gone up 5% since 2004, the percentage spent on every other expenditure has been on a downward trend. That is, even as the pie has increased in size with higher tuition, the administration has focused on spending proportionally more on faculty salaries, rather than spreading the money evenly throughout expenditures.

The 5% increase in faculty salaries since 2004 translates to an increase of more than $3.5 million in just 7 years. With the assumption that professors likely take home most of this pay increase (though not all of it), it averages out to roughly $55,000 extra per professor*. For a professor hired in 2004 at the standard faculty starting salary of $100,000 a year, this would be a 55% salary increase over a 7 year period. Additionally, during the 3 years prior to that, each professor received an average of roughly $15,000 extra in salary, for a total 70% increase in salary over the 10 year period (2001 to 2010)**. Whether or not you think that is too much is up to you but I think the more important question is: what was the reasoning behind the salary increases?

The salary increases were not the result of normal course of business raises that occurred regularly. Before I explain the reasoning given, let’s just review a little history. The movement to increase tuition (and salaries) started after the Ontario government deregulated tuition for professional programs in 1998. Our Dean at the time, Ron Daniels, immediately pushed for a raise of tuition from $3808 to $12,000 by 2001. Dean Daniels then pushed for a $10,000 increase in tuition over a 5 year period, to $22,000 in 2006. Since then, first year tuition under Dean Moran’s tenure has increased by 8% per year consistently to the $28,595 it is now***.

From what I can gather, the first set of tuition increases (from 1998 to 2001) was met with moderate but not extreme resistance, as it seems to have been motivated to a fair extent by reasons other than professor salary increases. The plan was to lower the faculty-student ratio, offer new courses, renovate classrooms and offices, better fund student services (especially DLS), increase the number of foreign placements from IHRP, launch PBSC, and increase staff at the CDO. All of this seems to have been accomplished.

The second and third set of tuition increases (2001 to 2006 and 2006 to the present) were met with more resistance, as different reasoning for increased tuition was stated – primarily, to increase in faculty salaries. Increased salaries were meant to retain and attract the best professors so that we could become one of the “leading law schools of the world”, to quote former Dean Daniels. The argument was that if we don’t pay our professors similar salaries, they will take jobs at top ranked American schools or in the private sector and we won’t be able to recruit scholars away from those same entities. Essentially, former Dean Daniels wanted us to become the Harvard of Canada.

On its face, former Dean Daniels’ argument makes sense. Most of our professors could easily double their salaries on Bay Street or make more money at an American law school. However, I believe there is a lot of evidence to cast suspicion on that logic. First, in the 10 years before the second set of tuition increases (primarily focused on increasing professor salaries), we lost only three professors to American schools. Second, even as professor salaries increased 55% after tuition hikes, we lost the same number of professors to American schools (plus one, if you count Dean Daniels). Dean Daniels, who warned that higher American salaries would attract our faculty, left UofT for a higher American salary (former psych majors can speculate if he was simply projecting his own insecurities). Third, while we lose twice as many professors to other Canadian schools than to American schools, the faculty explanation is always that those professors were not leaving for money but rather found a better “fit” – this makes sense since most other Canadian law schools pay less on average. Fourth, the professors generally accepted as making us the top ranked school in Canada – Waddams, Trebilcock, Weinrib, Stewart, Roach, Shaffer, Macklin, Rogerson, Oosterhoff, etc – have all been here since before the major salary increases (and most since long before). Lastly, as argued by professors Shaffer and Phillips 10 years ago when they opposed the tuition increases, though professors can certainly make more money on Bay Street, they chose to be professors and “get the incalculable benefits of a life of teaching and research, a life without the demands of clients and the need to bill every 10 minutes of their time.” In fact, many of our professors choose never to practice at a firm because being a professor is likely a calling they desire.

To me, all of the above evidence casts a lot of doubt on the need to have professor salaries that rival those of Bay Street or Harvard. If we lost almost the same number of professors to American schools before and after the salary increases, they do not seem to have done much. Of course, it’s possible that we were able to retain many professors by offering them the higher salaries (i.e. it stopped the floodgates from opening). Moreover, it’s possible that a generational shift in attitudes toward work flexibility means that younger professors require competitive salaries to stay at our school. However, I personally believe that since more professors leave for better fit at other (generally lower paying) Canadian schools, our “top professors” have all been here since before the salary increases, and many professors find their calling in academia, competitive salaries are unnecessary to retain faculty. Nonetheless, this is not something I can argue with absolute certainty. I do believe that the question of whether competitive salaries are effective needs to be asked though and that those “on the left” are right to do so.

It is entirely possible that the strategy of making UofT into the Harvard of Canada will work in the long-term. We may one day attract as many prominent American and international academics as former Dean Daniels hoped we would. And this may propel UofT to become one of the world’s leading law schools. And we may need higher tuition to pay the higher salaries. But it is also entirely possible that the result will instead just be higher professor salaries and a student body populated by the wealthy and those willing to take the risk of paying over $40,000 in first year tuition (which is scheduled to occur in the 2017/2018 academic year at current rates). The administration has offered little to prove the first situation is more likely – our hire rate is falling, we still lose professors to American and Canadian schools, the number of distinguished visiting faculty has decreased, and we have yet to attract many new prominent legal scholars away from other schools.

It is our job as current students to question the faculty and make them prove that higher tuition will, in fact, lead to a better school. Will we really attract enough new prominent professors to raise our reputation to that of Harvard or will the professors who were already here continue to be our beacon? Will financial aid keep up with tuition or will it continue to grow 20% slower? Will many students go elsewhere because they cannot afford UofT? Will our students feel pressured to go to Bay Street instead of the public sector because of higher tuition? Do we really need to compare ourselves to American schools? Is raising tuition and professor salaries the best way to become a world leading law school? I am certainly not automatically against tuition increases but before these questions and others are answered, I do not believe they should be blindly accepted as justified.

*[$3,561,668 – assumed $206,668 for research support salary increases] / estimated 61 professors = $55,000 per professor

**Martha Shaffer & Jim Phillips’s calculation that each professor would get a $30,000 increase from 2001 to 2006, subtracting the amount already incorporated in the above calculation for 2004-2010

***Including incidental/ancillary fees