Admissions play an enormous role in the life at the law school. For 44 years Prof. Arnold Weinrib chaired the admissions committee and used his many decades of experience, along with the judgment of the committee, to determine who should be admitted.

This year, Prof. Weinrib stepped down and Associate Dean Alarie took over as chair of the admissions committee. As Alarie puts it, “there was no way for me to put Arnold’s wisdom into my brain,” necessitating a new system.

The new system relies less heavily on human judgment and more heavily on data and algorithms. Applicants are assessed on two main factors: their academic record and their personal statement / autobiographical sketch. Academic record is weighted 2/3s and personal statement / biographical sketch are together weighted 1/3.

A number of factors are assessed when determining the strength of an applicant’s academic record. Most important is the student’s undergraduate GPA, but that GPA is adjusted to control for the program and school in which the GPA was earned. Academic strength also includes whether the student holds a graduate degree.

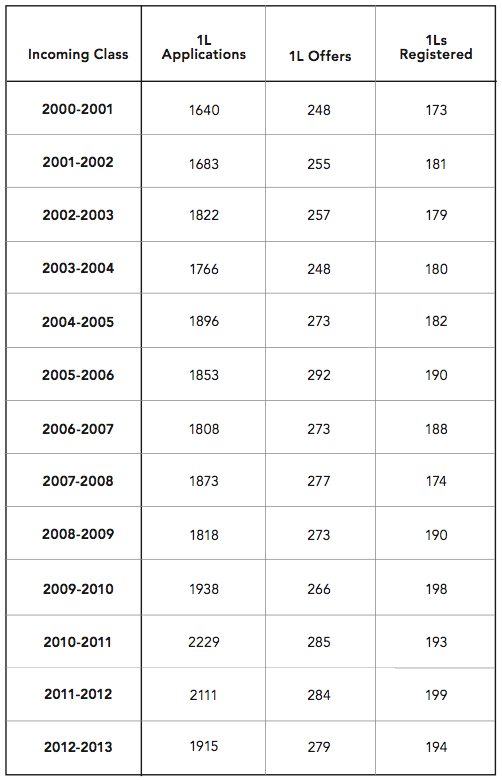

Academic strength is not determined subjectively by the admissions committee, as it once was, but instead by an algorithm using data from the past 10 years of students at U of T. The algorithm compares everything that was included in the applicant’s application with their grades at law school. The algorithm can then determine what factors best predict the success of a student in 1L and can assess the predictive value of GPAs from different undergraduate programs at different institutions. It has found that GPA and LSAT scores are of essentially equal predictive value but that the presence or absence of graduate work is only weakly positively correlated with success in 1L.

The introduction of this algorithm may admit people with low GPAs from difficult programs that would not otherwise meet the GPA thresholds at U of T. It is this aspect where Alarie invites the comparison to moneyball: while these candidates may have a lower GPA, they are actually academically stronger than some applicants with higher GPAs from less difficult programs. Therefore U of T can admit qualified applicants that the process might have otherwise overlooked. Alarie says, “while our median GPA may slip somewhat this year, using these data we will hopefully admit a more academically accomplished class.”

Subjective human judgments, however, are still needed to assess the personal statement and autobiographical sketch of each applicant, which accounts for 1/3 of the admissions decision. There are no autoadmits: every applicant who is admitted to U of T law has their personal statement read by the committee.

Each personal statement is read by multiple members of the committee and scored out of 4. Those scores are then entered into the algorithm which then ranks candidates based on the score of the committee combined with the index of academic strength. Offers are then made to applicants moving down that ordinal list.

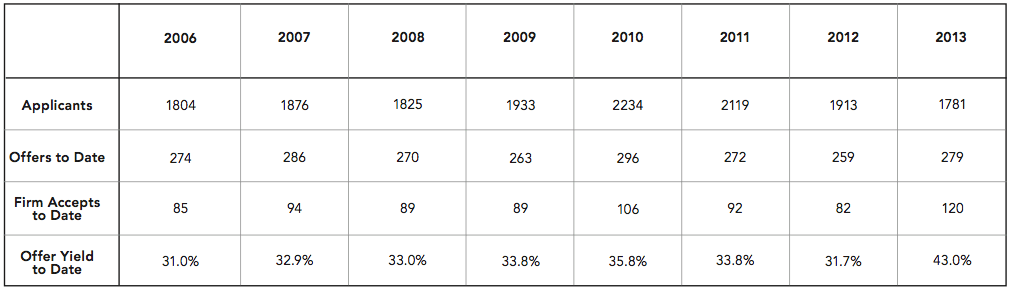

The percentage of applicants who accept U of T’s offer of admission is referred to in admissions circles as the “yield.” U of T law’s yield, 70.6% last year, is among the highest on the continent. Yale Law School’s yield, the highest in the US, is 80.4%. Harvard Law School’s yield is 67.3%. In Canada, according to Recruitment & Admissions Coordinator Vicky Faclaris, Osgoode Hall’s yield is approximately 52%.

The yield at U of T has remained constant despite the increase in tuition and the increasing number of students receiving large merit scholarships from US schools. U of T is at a disadvantage when recruiting these candidates because almost all of U of T’s financial aid is needs-based. Nevertheless, U of T manages to recruit excellent students and Alarie conjectures that “we probably win every head-to-head contest—there are more students at U of T who turned down Harvard than students at Harvard who turned down U of T.”

There are encouraging signs that the upcoming building project is not adversely affecting yield. Typically by mid-march approximately 33% of applicants have accepted U of T’s offer of admission (see chart). This year, 43% have. Alarie credits this jump to the admitted student events in the faculty held this year in Ottawa, Montreal, Calgary and Vancouver as well as the revamped Welcome Day at the faculty which an unprecedented number of prospective students attended.