Daanish Samadmoten (Alumnus, Class of 2014)

Yes, you did. At least if you plan to work in “public interest” after graduation. According to a mathematical model I created with a fellow alumnus, if you work in public interest after going to U of T Law, you will make almost $100,000 less over 20 years than you would have if you started working immediately after undergrad in another field. The average return on your investment (going to U of T Law) is -3%. For the purpose of this article and the model, public interest is intended to include human rights lawyers, duty counsel, criminal defense lawyers whose clients primarily use legal aid certificates, etc. The starting salary for a public interest job was thus set at $60,000.

The above numbers don’t even reflect the pay “cut” one takes by choosing public interest over Bay Street. It’s no wonder then that some students complain about feeling pressured to work in jobs outside of public interest – to work in public interest, you have to be willing to lose money on your investment and forego a large income.

The “pressure” not to work in public interest due to U of T Law’s high tuition was a big part of the tuition debate while I was at school. The pressure is financial so I reframed the problem and asked: does it make financial sense for you to go to U of T Law and then work in public interest? The answer depends on a large number of factors so we created a mathematical model in hopes of answering it. The model incorporates lost income while going to U of T Law, tuition, debt repayments, interest on debt, average tax rates, summer income while in school, articling income, salaries, salary inflation, salary caps, inflation, and a discount rate.

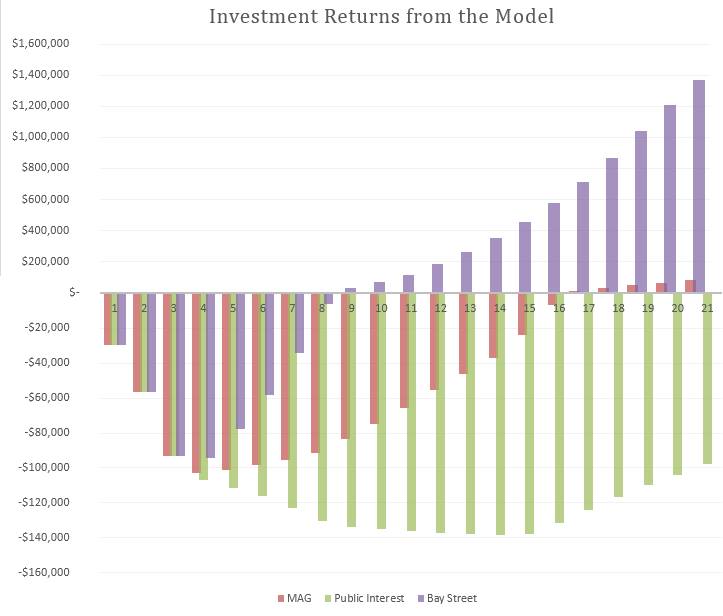

Based on the model and the assumptions used, you would have been better off starting work after undergrad in another field instead of going to U of T Law and then working in public interest. As stated above, on average, you are losing $97,818 over 20 years by going to U of T Law instead, using our discount rate of 5%. However, the return is dramatically different if you work on Bay Street. Using the model, going to U of T Law and then working on Bay Street yields an average $1,370,297 return over 20 years.[i] That is a 32% rate of return. If you work at the Ministry of Attorney General (MAG) after U of T Law, your investment yields an average $80,947 return over 20 years, which is a 10% rate of return.[ii]

To show how the model translates in real life, let me give you a brief example. According to the model, a student that started U of T Law this year who goes on to work in public interest after graduation will be making $54,625 post-tax ($72,930 pre-tax) as a fifth year lawyer. They will pay off $10,000 of their remaining $60,232 law school debt that year and will have accumulated $16,476 in interest on that debt thus far. Eight years after starting law school (five years after graduating), they have made $133,588 less than they would have at that point, if they had started working immediately after undergrad in another field.

All of these numbers don’t necessarily mean you shouldn’t work in public interest, though. Financial return is only one part of a value calculation. There may be intangible benefits that you would not get elsewhere. Perhaps a feeling that you enjoy what you do. Or that you are making a difference and doing something worthwhile. Plus, compared to the relevant alternative (not going to law school and starting work), you are more educated and get other intangible benefits. The intangibles will vary from person to person but they certainly exist. And there’s nothing foolish about considering them alongside the financial return; education isn’t a purely financial investment.

Some people may be willing to deal with the financial pressure of working in public interest after graduation because they value the intangible benefits more than the financial loss. However, increasing tuition will increase the financial loss and thus increase the pressure. Tuition debt is a particularly strong pressure because it is tangible and noticeable – it is sitting there in your bank account accumulating interest. More people are likely succumb to that pressure as tuition increases and choose to work outside of public interest, which will decrease the career diversity amongst U of T Law’s graduating class.

I should note that the model is not perfect or even necessarily correct. It relies on a lot of assumptions that are open for debate, such as salary caps, salary inflation, salary promotions, and amount of debt repayment per year. I used my intuition for many of the assumptions and hard data for some. A case can certainly be made that some of my intuitions were wrong and thus the assumptions should be changed. The model is included here so feel free to download it and play around with the assumptions if you disagree with them – the returns will change automatically so don’t worry about your Excel aptitude.

Despite its inevitable imperfections, I think the model provides interesting results and a framework in which to answer the question at hand, though it does not provide a necessarily correct answer. Even if you change some of the most influential assumptions in the model, I do not believe that the returns change so significantly that the overall point is invalid. Going to U of T Law is a huge investment; you have to put in your time, effort, and money while foregoing money you could have been earning. It is certainly a bigger commitment than almost all the other financial investments in your life. If the investment yields a negative (or even a slightly positive) return by working in public interest and involves significant pressure from tuition debt, then some people will undoubtedly be pushed away from that path. If U of T Law doesn’t want to be a school with graduates that work almost exclusively outside of public interest, the administration must do something to address this problem caused largely by high tuition.

[i] The model uses $100,000 as the starting salary of a Bay Street lawyer, which is typical of most Bay Street firms.

[ii] The model uses $76,000 as the starting salary for a MAG lawyer, as told to me by first year counsel at MAG.