Rona Ghanbari (3L)

“If we fail in our duty of care to the smallest and most vulnerable among us, then we fail the most basic test of justice and compassion.”

- Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, Ralph Goodale [1]

The Canadian human rights brand – are we living up to our reputation?

Living in Canada, many of us enjoy fundamental human rights that are rigorously protected by the law. In watching the news or discussing egregious breaches of basic human rights elsewhere in the world, many Canadians feel fortunate, or perhaps even morally superior to those in other nations. Unfortunately, Canada’s reputation as a defender of human rights has been blemished egregiously on several fronts, among which is its immigration detention regime. In recent years, Canada has held hundreds of children in immigration detention, and they have suffered immensely, unseen and unnoticed by the Canadian public. Some of these children are from Syria or other war-torn regions, and others are Canadian citizens who are not formally detained but live in detention centres to accompany their detained parents. In detention, these children are denied proper education, the opportunity to socialize with other children their own age and make friends, and sometimes they are even placed in solitary confinement. This is no way for a nation that is a world-renowned leader in human rights to treat such a vulnerable group.

On September 22nd 2016, the University of Toronto’s International Human Rights Program (IHRP) released a 70-page landmark report titled “ ‘No Life for a Child’: A Roadmap to End Immigration Detention of Children and Family Separation.” The report uncovers the state of child detention in Canada by providing statistics, featuring interviews with those who have been detained, explaining the severe and lasting mental health consequences of child detention and family separation, and providing recommendations for community-based alternatives to detention and family separation. No Life for a Child continues the IHRP’s advocacy focus on immigration detention, which began with the 2015 report, “ ‘We Have No Rights’: Arbitrary Imprisonment and Cruel Treatment of Migrants with Mental Health Issues in Canada.” No Life for a Child was researched and written by IHRP Senior Fellow Hanna Gros and IHRP fellow Yolanda Song, and edited by IHRP Director Samer Muscati, among others.[2] The report contains much more detail and information on the issue than could be highlighted in this article, and is a compelling and shocking account of Canadian immigration detention practices.

The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC) has criticized Canada on numerous occasions – most recently in 2012 – because of its child detention practices.[3] Specifically the CRC condemned the scale of child detention in Canada, and the inadequate consideration for the best interests of children.[4] The United Nations Human Rights Committee, refugee rights groups, and child rights advocates have also criticized Canada with respect to its child immigration detention practices. In response to criticism of detention practices in Canada, Canada’s Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, Ralph Goodale, has stated that Canada will commit to “avoid housing children in detention facilities, as much as humanly possible.”[5] No Life for a Child calls for action that goes further than that, stating:

“It is crucial…that family separation is not instituted as an alternative to detention. The practice of detaining parents without their children is not an acceptable alternative to housing children in detention facilities because family separation also inflicts serious psychological harms on children.”[6]

Canadian Child Detention – Simply Put

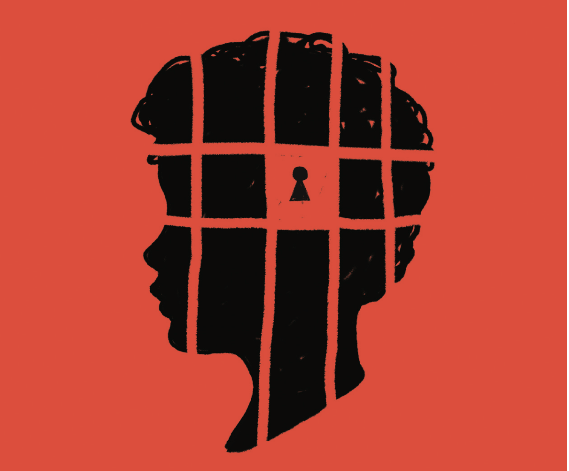

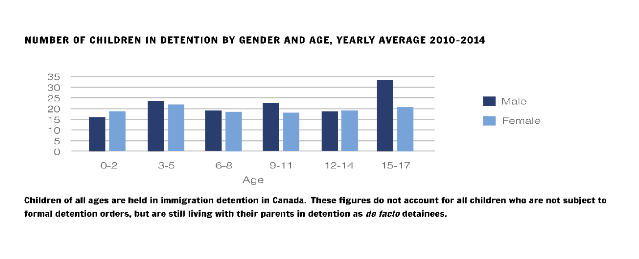

Figures obtained by the IHRP through access to information requests revealed that an average of 242 children were detained yearly between 2010 and 2014.[7] This figure is an underestimate because it does not account for all the children who are living with their parents in detention as “guests” who are not themselves formally detained.[8] Some of these children are Canadian citizens who have no option but to either live with their parents in de facto detention, or to be taken to child protective services.[9] Some children were even born into detention.

Detainees are held in Immigration Holding Centres (IHCs). These are medium-security facilities where children and their families have restricted mobility, are subject to constant surveillance, and are searched frequently. Children do not have access to adequate education. One detainee reported that an IHC teacher would come three times a week to teach children between the ages of four to nineteen.[10] This is unacceptable given the vast diversity in needs among children of different ages. Some of these children spend months in detention, making the lack of access to adequate education even more consequential. Furthermore, children rarely get the opportunity to socialize with other children their own age and develop friendships, and they are only allowed to go outside for short periods of time.

Although some children are in detention as an alternative to family separation, the latter is not entirely mitigated in detention. Family rooms in the IHCs are restricted to mothers and children,[11] which means that children are separated from their fathers, and may only visit them for short periods each day.[12]

Research demonstrates that living in detention causes serious psychological harm to children. Constraining a child’s liberty and privacy for extended periods of time while also providing them with extremely limited contact with other children or with educational or recreational activities has severe mental health consequences. Children who have lived in detention demonstrate increased symptoms of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and suicidal ideation. Many of these children also develop behavioural issues and become more angry or irate. Separating children from their parents – whether by detaining only their parents, or detaining them in a separate wing within the detention facility – is profoundly harmful for a child’s mental health as well. The stressful conditions under which they live, along with the pervasive under-stimulation and boredom, “create a sense of deprivation and powerlessness among children,” which often results in mental health issues which persist after release from detention.[13]

Where children are not accompanied by their parents or guardians, they may be placed in solitary confinement. Solitary confinement means physical and social isolation for at least 22 hours per day.[14] Solitary confinement is extremely detrimental to an adult’s mental health, and even more detrimental for the health of a child, as confinement can have a profound impact on a child’s brain development.[15] To a child, a few days in solitary confinement may feel like several weeks.[16] Solitary confinement of children is strictly prohibited by international law. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture has stated that placing a child in solitary confinement for any length of time violates the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and well as the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.[17] The CRC has stated that under the Convention on the Rights of the Child solitary confinement should be “strictly forbidden” for children. Canada has been failing to meet its international human rights obligations.[18]

IHRP Director Samer Muscati remarked that, “[t]he immigration detention of children does nothing to increase public safety, but has an immensely detrimental and lasting impact on an already vulnerable population.” This powerful statement highlights the arbitrariness of the practice, and the urgent need for its cessation.

Voices from the inside

In conducting research for No Life for a Child, the IHRP interviewed and profiled mothers and their children in detention. Many of the parents provided heartbreaking stories of the trauma their children endured during and after detention. One mother, who had been detained for 6 months at the time of the interview, explained that that her son had become “angry about everything”; he said that he was “locked in these walls,” and cried during the night.[19]

Another example is the devastating account of a 16-year-old Syrian boy, who arrived in Canada unaccompanied by his parents, with hopes of seeking asylum, only to be taken to a detention centre and placed in solitary confinement for three weeks. During his time in detention he was not allowed to contact his family and was only allowed outside for 30 minutes a day. “Canada government brings many people from Syria, Jordan and Lebanon, Turkey, but I am coming here, and they don’t accept me,” he said. “Three weeks in detention, I’m feeling sad, and I cry all the time. The room, the iron on the windows, I’m afraid.”[20]

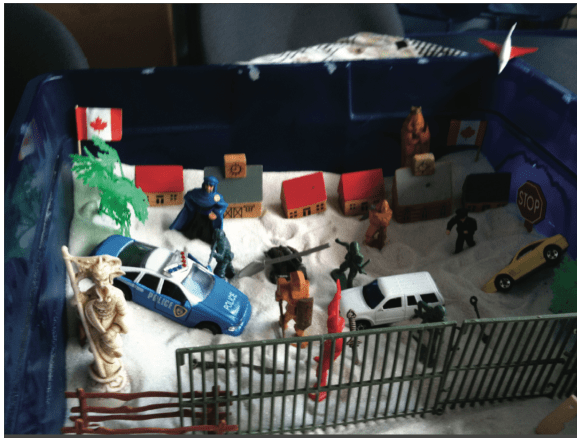

The report also highlights mental health research examining the effects of detention on children using interviews or activity-based data collection. One research method was sandplay, where children were given various figures and a mini sandbox within which they were asked to build a world. The lives the children created in their sandboxes exhibited the trauma they carried with them during and after their detention.

© Rachel Kronick

© Rachel Kronick

What is the legal basis for detention/family separation?

A person may be placed in immigration detention if a Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) officer has reasonable grounds to believe that they constitute a flight risk or a danger to the public, or if their identity is not established. Immigration detention in Canada is implemented under the authority of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA)[21] and its Regulations.[22] CBSA initiates the decision to detain someone, and the Immigration Division of the Immigration and Refugee Board adjudicates detention review proceedings with CBSA’s participation.[23] Both bodies rely not only on the legislation but also on policy guidelines to interpret provisions and make decisions with regard to immigration detention.[24] Unfortunately, the legislation and policy guidelines do not prohibit the detention of children or provide a limit on the length of time individuals can be detained. Instead, IRPA requires that decision-makers consider the best interests of the child as one of several factors in detention-related decisions. The Convention on the Rights of the Child requires that authorities take into account the best interests of the child as a primary consideration in all state actions concerning children, and Canada’s treatment of children in the context of immigration detention is clearly falling short of this standard.

So, what are the solutions?

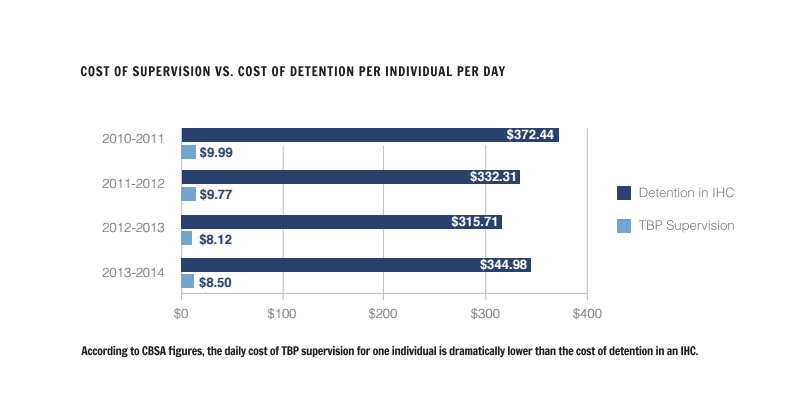

CBSA officer and Immigration Division adjudicators are given broad discretion to impose whatever conditions they feel are necessary or unnecessary with respect to detention, and they are required by law to consider all reasonable alternatives to detention before making a detention-related decision.[25] IHRP director Samer Muscati commented, “[i]nstead of locking children up or separating them from their detained parents, these children need meaningful protection in community-based alternatives to detention.” Community-based alternatives to detention ensure that fundamental rights are better protected as individuals are treated with dignity and respect, and family separation (which has extreme negative mental health effects) can be eliminated altogether. Community-based alternatives are also significantly more cost-effective than detention. CBSA spent an average of nearly $21.5 million each year between 2010 and 2014 on IHCs.[26] By contrast, the cost of a community-based alternative, such as the Toronto Bail Program (which supervises individuals while they reside in the community), costs approximately $1.1 million a year.[27]

No Life for a Child reviews and details several alternatives to detention programs, such as reporting obligations, financial deposits and guarantees, third-party risk management programs, open accommodation programs, and electronic monitoring. The report also outlines and analyses best practices used in other countries. The most important aspect of these programs, however, is keeping families together outside of detention centres.

No Life for a Child provides eleven recommendations that complement and build upon the recommendations made in the 2015 report, We Have No Rights. Because discretionary powers exist under the IRPA, authorities are able to implement the goals of these recommendations immediately, before passing legislation. Among other things, the recommendations involve revising legislation, regulations, and practices to reflect international standards with respect to the best interest of the child.

The Canadian federal government and CBSA have engaged with the IHRP and have indicated a strong willingness to reform the immigration detention regime, with particular emphasis on protecting children. The report’s co-author, Hanna Gros, stated: “After years of silence and inaction, the Canadian government and CBSA are taking serious steps that will hopefully bring us closer to ending child detention and family separation, but Ottawa needs to move quickly and deliberately to end the needless suffering of children and their parents.”

If the Canada wants to be a leader in human rights on a global scale, we cannot turn a blind eye to the mistreatment of an extremely vulnerable group within our own borders.

Access the full version of No Life for a Child here: <http://ihrp.law.utoronto.ca/utfl_file/count/PUBLICATIONS/Report-NoLifeForAChild.pdf >

———————————————————————————————————-

[1] Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, Press Conference at Laval Immigration Holding Centre, “Detention program and infrastructure announcement” (15 August 2016).

[2] Rachel Kronick of McGill University also contributed significantly to the research and writing of this report, along with many others. The full list of acknowledgements is available in the full report.

[3] United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, Concluding observations on the combined third and fourth periodic report of Canada, 61st Sess, UN Doc CRC/C/CAN/CO/3-4 (5 October 2012) at para 73.

[4] Ibid at paras 34, 73–74.

[5] Public Safety Canada, News Release, “Statement by the Honourable Ralph Goodale, Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, on Immigration Detention” (19 July 2016), online: <http://news.gc.ca/web/article-en.do?nid=1101379> .

[6] No Life for a Child, at p 9 <http://ihrp.law.utoronto.ca/utfl_file/count/PUBLICATIONS/Report-NoLifeForAChild.pdf >

[7] Ibid at p8.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Canada Border Services Agency, Information for people detained under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (2015) at 1, online: <http://www.cbsa-asfc.gc.ca/publications/pub/bsf5012-eng.pdf>

[10] No Life for a Child, at p 10 <http://ihrp.law.utoronto.ca/utfl_file/count/PUBLICATIONS/Report-NoLifeForAChild.pdf >

[11] Canadian Red Cross Society, Annual Report on Detention Monitoring Activities in Canada, Confidential (2012–2013) (obtained through access to information request by IHRP, A-2014-12993) at 20

[12] Rachel Kronick, Cécile Rousseau and Janet Cleveland, “Asylum-Seeking Children’s Experiences of Detention in Canada: A Qualitative Study” (2015) 85:3 American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 287 at 290; Janet Cleveland, “Not so short and sweet: Immigration detention in Canada,” in Amy Nethery and Stephanie J Silverman, eds., Immigration Detention: The Migration of a Policy and its Human Impact (New York: Routledge, 2015) at 96

[13] No Life for a Child, at p 5 <http://ihrp.law.utoronto.ca/utfl_file/count/PUBLICATIONS/Report-NoLifeForAChild.pdf >

[14] United Nations General Assembly, Interim report of the Special Rapporteur of the Human Rights Council on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, Juan Mendez, 66th Sess, UN Doc A/66/268 (5 August 2011) at para 26.

[15] UNGA, Interim report of the Special Rapporteur on torture, supra note 13 at para 55.

[16] Office of the Provincial Advocate for Children and Youth of Ontario, It’s a Matter of Time: Systemic review of secure isolation in Ontario youth justice facilities (2015) at 16, online: <https://provincialadvocate.on.ca/documents/en/SIU_Report_2015_En.pdf>.

[17] Email from Canada Border Services Agency (12 August 2016).

[18] United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, General Comment No. 10: Children’s rights in juvenile justice, 44th Sess, UN Doc CRC/C/GC/10 (25 April 2007) at para 89.

[19] No Life for a Child, at p 9 <http://ihrp.law.utoronto.ca/utfl_file/count/PUBLICATIONS/Report-NoLifeForAChild.pdf >

[20] Maureen Brosnahan, “Syrian boy seeking refugee status ordered deported to United States,” (16 February 2016) CBC News, online: <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/syrian-teen-detained-toronto-1.3449595> [Brosnahan, “Syrian boy ordered deported”]; IHRP interview with Andrew Brouwer, Senior Counsel – Refugee Law, Legal Aid Ontario (5 August 2016)

[21] Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, SC 2001, c 27, ss 54–61.

[22] Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations, SOR/2002‐227, ss 244–251.

[23] Canada Border Services Agency, “Acts, regulations and other regulatory information: Delegation of Authority and Designations of Officers by the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act and the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations” (26 July 2016), online: http://www.cbsa-asfc.gc.ca/agency-agence/actreg-loireg/delegation/irpa-lipr-2016-07-eng.html; Citizenship and Immigration Canada, “ENF 3 Admissibility, Hearings and Detention Review Proceedings” (29 April 2015) at s 7, online: <http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/manuals/enf/enf03-eng.pdf> .

[24] Canada Border Services Agency, “Operational bulletins and manuals” (27 June 2016), online: <http://www.cic.gc.ca/English/resources/manuals/index.asp>; Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, “Policy on the use of Chairperson’s Guidelines” (27 October 2003), online: <http://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca/Eng/BoaCom/references/pol/pol/Pages/PolGuideDir.aspx>.

[25] Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations, SOR/2002‐227, s 248(e).

[26] No Life for a Child, at p 40 <http://ihrp.law.utoronto.ca/utfl_file/count/PUBLICATIONS/Report-NoLifeForAChild.pdf >

[27] Ibid.