Aidan Campbell (2L)

Finally, imagine a school in which no student who can gain admission on the merits will be excluded on the basis of financial need and where students can make career choices not burdened by student debt servicing costs.

This was the linchpin of former Dean Ron Daniels’s defence of our law school’s plans to rapidly increase tuition in a National Post editorial back in 2001. Yes, the school will be more expensive to attend for some but, through a robust financial aid program, accessibility will not be affected. Many within the faculty did not believe this at the time, most notably Professors Philips and Reaume, who wrote a joint response piece in the National Post.

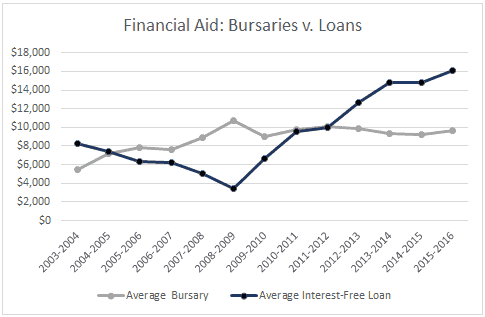

Fifteen years later it’s worth revisiting this promise. To that end, Ultra Vires has compiled financial aid reports released by the faculty from the 2003-04 year through to 2015-16. The results put lie to the idea that financial accessibility has not been a casualty of excellence.

First, the promise that 30% of all new tuition increases be set aside for financial aid has long been abandoned. The average bursary provided to students who qualify for financial aid has remained flat for years, hovering between $9,000 and $10,000 since 2007-08. This means that, despite a provincial cap on tuition increases of 5% since 2013-2014, tuition has effectively increased by 9% annually for first years who applied for financial aid in the years since 2013-2014. Debt has filled the gap, with average interest-free loans growing from $5,087 in 2007-08 to $16,098 in 2015-16 (15% annually).

In his editorial, Daniels bragged that thirty-five students were attending the faculty tuition-free in the 2001-02 school year. Free tuition is a thing of the past: the last time the faculty had students on full bursary was 2009-10, when the faculty made a policy choice to distribute aid more broadly and less progressively.

The back-end debt relief fund, meant to be the final bulwark against debt influencing career choice, has been similarly stagnant, frozen at $285,000 (distributed among all alum still accessing the program) since 2012. Over the same period, the average eligible debt load of participants in the back-end debt relief program has risen from $31,756 to $41,599, with the average participant’s salary staying relatively constant. So yes, obviously some students are still deciding to take lower paying public interest work; but in making that choice they are deciding to be more indebted, for a longer period, than those who came before them. To argue this debt load creates no disincentive to follow such a path would not pass muster in an undergraduate paper, let alone be honestly believed by a faculty full of specialists in law and economics.

Things are even getting harder for students who make the economically rational decision to ply their craft on Bay Street to pay down their debt. Salaries for first year associates at Toronto’s biggest firms have not significantly changed since the recession. Shedding tears for twenty-somethings making twice the nation’s median household income is not something we make a habit of, but tuition deregulation took place immediately following the 90’s boom in lawyer salaries. It is obvious that the economic calculus that enabled endless tuition increases has fundamentally changed.

Finally, something that may not be immediately apparent in the financial aid statistics is how an increased reliance on private credit openly excludes anyone with a troubled credit history. These students are forced to avail themselves of the ad-hoc and nontransparent emergency loan system that the faculty oversees.

None of these observations are particularly new, and members of the administration are used to batting away questions of accessibility by citing increased applications and higher rates of accepted admissions offers. Neither of these addresses the question of who isn’t applying, nor the socio-economic breakdown of those who are.

In response to Daniel’s editorial, Professors Reaume and Phillips wrote that:

We may also become less vigilant guardians of the shape of the legal profession and of accessible legal education. Linking faculty salaries and tuition fee increases means we contribute to the problem of distorting students’ career choices—they simply have to take the jobs that enable them to pay off their increasingly large debts.

The faculty’s own financial aid statistics shows that this has indeed come to pass. It is time that we recognize this and start seriously considering a new model.

Next month: Where did all the money go? A deep dive into the sunshine list.

And stay tuned for Part Three as we take a look at the pros and cons of various alternative funding models.

Background reading:

https://www.law.utoronto.ca/documents/Phillips/higher_tuition.pdf

https://ultravires.ca/2013/03/the-price-of-excellence-a-discussion-document/

https://ultravires.ca/2016/03/towards-constructive-tuition-debate/