A history of a wine club

Photo credit: Tom Collins (2L)

One of my favourite scenes in the film This is Spinal Tap is the introduction to Stonehenge.

“In ancient times, hundreds of years before the dawn of history, lived an ancient race of people—the druids. No one know who they were, or what they were doing, but their legacy remains, hewn into the living rock …”

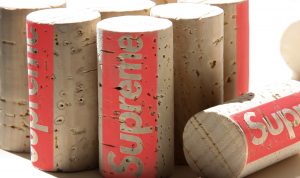

This summer, I had my own Stonehenge moment, when Professor (and faculty sage) Jim Phillips told me that before In Vino Veritas there was another wine club: The Supreme Cork. I laughed but, knowing Professor Phillips’s penchant for witticisms, I was unsure whether he was simply trying out some new material. Could an ancient race of law students really have come up with such a corny name? Yes. But why? I decided to investigate.

My journey took me deep into the moldering archives of the law school. Picture a scene from The Cask of Amontillado. The archives are nothing like that, but Poe’s imagery will make for a much more evocative experience. I figured that if any record existed of The Supreme Cork, it would be in Ultra Vires—a storied publication, easily on par with the Times, but with more pictures of cute animals. After exhuming the delicate vellums on which the early editions were printed, I worked tirelessly by candlelight for at least ten minutes.

To my surprise, people at the turn of the millennium wrote much as we do today. I pondered what wealth of mystical wisdom lay between these yellowed pages. One comment from a 1999 issue read, “fees need to go down, financial aid up.” I digress.

The precise origins of The Supreme Cork have been lost to their own drunken haze. It was formed circa 1998, but the first known reference to it appears in the first publication of Ultra Vires from September 1999. It is only a brief mention of the society’s existence. No names are given, but the blurb alludes to people “who claim to have acquired a vast knowledge of international wines” by participating in the society. The author then quips that after half an hour, “neophyte wine-tasters will be amazed at how fascinating, witty, and attractive their classmates have suddenly become.”

The next mention of The Supreme Cork bookends its short existence. In March 2005, Adrian Liu (3L) lamented the death of the society, which had existed only in name and SLS funding provision since late 2004. Apparently, the club’s “heart and soul” had gone with alumnus Daniel Anthony, now a barrister and solicitor in patents and trademarks at Smart & Biggar’s Ottawa office.

I reached out to Daniel, who was the society’s president from 2002 to 2004, to see what I could learn. Daniel, it turned out, was a fount of knowledge. He was proud of his involvement and was eager to share his recollections with me. I was inspired by what I learned.

Daniel told me that, during his tenure, the society was somewhat like our own wine club, In Vino Veritas, in that it had no official membership beyond a small executive board. However, it never published anything substantial like wine reviews. Instead, The Supreme Cork’s focus was on events. It hosted about eight events, all wine tastings, over the course of Daniel’s presidency. Those usually drew a little over a dozen students. Yet, what is really interesting is that he hosted all of those tastings at school, something that In Vino Veritas has been all but forbidden from doing.

Was the Faculty of Law more lax in the halcyon days of the early noughties? Hardly. Daniel was simply a renegade. About twice per term, he would slip a mysterious unnamed man $130 for wine. The plug was, allegedly, a sommelier, and he may have worked at the LCBO. No one knew for sure. Regardless, that plug would show up to the law school, after hours, with seven or eight bottles. He would have three whites, three reds, and one or two others. Under the cover of darkness, Daniel and the plug would set up the tasting in Falconer 105 or in Flavelle House, off the main foyer. They would draw the blinds to avoid detection. Then, they would open the bottles.

The wines were served from a brown paper bag. The plug filled up the glasses. Then, he would give everyone a sort of scoring sheet, with numbers 1 to 8 down one side: a number for every wine. Everyone would smell the wine. They would swirl it around and have a taste. They would write their impressions. The dilettanti would then try to guess the cost of wine they were drinking. The reveal often led to shocked exclamations. Some $9 bottles of plonk drank more like $40 crus.

Despite The Supreme Cork’s popularity with students, over the years, the society received warnings and complaints from the University. It condemned the society, stating that it could not sell alcohol, that it needed liquor licenses, and that it could not book rooms at the school for such nefarious activities.

“I skirted these issues in various ways”, Daniel recalled, “sometimes not advertising a price, saying the entire amount was an honorarium to the sommelier, or not listing the venue in ads and only telling those who had paid where it was (i.e., in the law school) a few days before the event. It seemed dumb to me that the University was complaining about a group of students discussing wine when two to three times a week there would be an open bar in the Rowell room for some launch… or reception.”

Unfortunately, The Supreme Cork’s clandestine existence was ultimately, its downfall. An unnamed faculty member once attended one of the secret bacchanals. Although that tasting went on, the society was shut down within a year. And that was that.

But, like the druids’ Stonehenge, The Supreme Cork’s legacy has lived on in a name that, in spite of, or perhaps, because of its banality, refuses to be forgotten. Daniel is certainly happy about that. For him, the name was the best part.