Supreme Court of Canada Collection

Busts have long adorned the halls of the privileged and powerful, serving as mementos of victories by history’s oppressors over the oppressed. In the 19th century, stately English homes and London gentlemen’s clubs were decorated with the marble busts of British aristocrats who grew fat through the twin miseries of colonialism abroad and industrial exploitation at home. In antiquity, Roman politicians and military officials (read: war criminals who terrorized the peoples of the Mediterranean Basin) ornamented their villas with the busts of their warmongering and slave-owning ancestors. Even a long time ago in galaxies far, far away, busts – or more accurately, human bodies frozen in blocks of carbonite – were synonymous with Hutt gangsterism and Imperial triumphs over the Rebel Alliance.

Can the bust serve another – a more just – purpose? Is it possible to rehabilitate the bust from its long history as a trinket of power élites? Or is the bust’s function as an accessory of privilege central to its very existence?

Modern apologists of the bust – including those holding the reins of power at this very law school – would be quick to point out that virtually all facets of human civilization – including art and religion – have been appropriated or created by historical ruling classes for the perpetuation of their own power. Celebrating privilege is not central to the bust qua bust. Yet art and religion have also existed in spaces uncontrolled by the dominant classes, serving crucial functions for those who wish to dissent from and subvert the hegemonic élite. Where is the bust as a tool of dissent, of subversion?

The atrium of our law school illustrates not only the continued use of the bust as an accessory of the privileged class, but also of the law itself as a domain of society’s privileged.

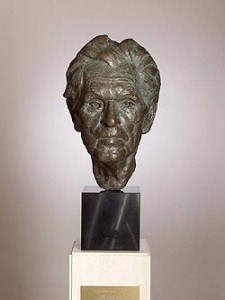

We proudly display the bronzed likenesses of Chief Justice Bora Laskin and Dean Cecil Wright (for whom this very column is named), figures who at once challenged power and were themselves embodiments of power. Laskin was a zealous liberal; rejected by the establishment of the day, he came to serve as Canada’s top judge and enacted reform at the tortoise-like pace permitted by activism through the judiciary. Wright himself brought change to this country by creating the modern law school. Aggressive, confrontational, and innovative, he founded a privileged institution that would create solicitors and thinkers who would also both be a part of and challenge that privilege.

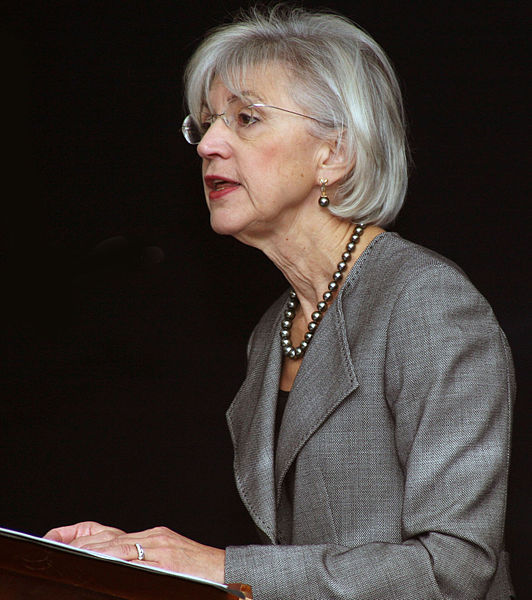

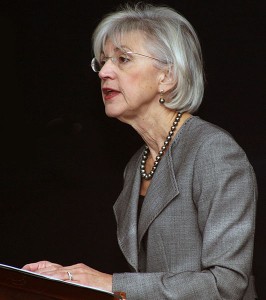

Our law school’s facilities are currently expanding and modernizing. As privileged law students, we will soon be replacing privileged undergraduates (tragicomedy at its finest) as we occupy Victoria College in the interim. This is a rare opportunity for renewal, and for a reform of which persons we choose to lionize and celebrate. Our current Chief Justice – Beverley McLachlin – is deserving of such an honour.

While a Puisne Justice, McLachlin made a name for herself as a civil libertarian voice on the Supreme Court. Her dissent in R v Keegstra, her judgment in R v Zundel, and her controversial ruling in R v Seaboyer denote a heart glowing with concern for individual rights and liberties.

And yet, in taking on Laskin’s mantle, McLachlin has led a Supreme Court that is at once progressive and cautious. Her drive for consensus rulings has been criticized from multiple angles: consensus produces unclear judgments; she could have achieved more progressive rulings with slimmer majorities; she is too policy-focused. Yet here is a Chief Justice who is the epitome of Fabianism – of gradual reform – and who attains social progress that is at once palatable to society and that is difficult to overturn.

Perhaps this paean to our current Chief Justice comes too early. While safe injunction sites are a noteworthy recent victory, battles over the decriminalization of prostitution and cannabis are currently being fought. In a country where political discussion of these issues is too taboo even for elections, achieving judicial consensus on them will be necessary if any social change is to be lasting.

The law – like the bust – is a tool of both power and privilege. Yet the law offers us an opportunity for social change – gradual, yes, but lasting social change. What better person to lionize in an atrium of privilege than one who both embodies that privilege and who uses it to create a more inclusive, tolerant, and equal society?

Note: The views expressed in the Wright Man do not necessarily express the views of Louis Tsilivis, although he is in support of a bust to Beverley McLachlin in the new law school buildings and does indeed the abhor the atrocities committed by the Galactic Empire against its subject-peoples.