In conversation with Bhavan Sodhi of Innocence Canada on the causes of Canadian Wrongful Convictions

The Criminal Law Students’ Association (CLSA) interviewed Bhavan Sodhi, Innocence Canada’s Legal Director and Director of the Innocence Project at Osgoode Hall Law School. Innocence Canada takes on the daunting task of investigating allegations of wrongful convictions and pursuing acquittals for the wrongfully convicted. As Bhavan made clear, a wrongful conviction — that is, the conviction of a person who is factually innocent — is the highest injustice our system can and does produce.

Although Bhavan took an indirect path to her current work, her reputation as someone who wanted to “do good” with her law degree served her throughout her career. She pursued an undergraduate degree in economics and international business. She never anticipated going to law school but ended up attending Osgoode after taking the LSAT on a whim. She joined the Innocence Project at Osgoode through her first-year criminal law professor and was hired back to work as an executive assistant.

After law school, impressed by their work on the Kaufman Inquiry into the wrongful conviction of Guy Paul Morin, Bhavan articled with Cooper Sandler Shime and Bergman LLP where she had the opportunity to work on other commissions of inquiry and systemic policy initiatives. She eventually found herself working as an Assistant Crown Attorney on youth and domestic matters when Kirk Makin contacted her asking her to join Innocence Canada. One of her former professors called her a “fanatical student who had a keen interest in wrongful convictions” and recommended her. Within a week, the Dean at Osgoode Hall Law School remembered the same thing and contacted Bhavan when the professor running the school’s Innocence Project retired. Bhavan has been in those complimentary roles ever since.

The Common Causes of Wrongful Convictions

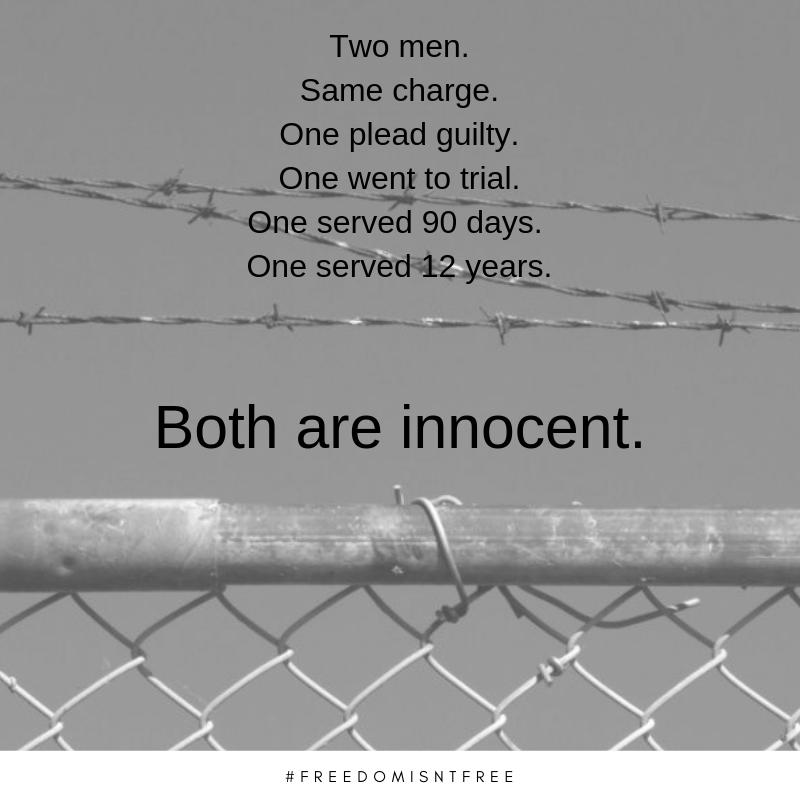

According to Bhavan, the most important thing to know about wrongful convictions is that they are not anomalous. Wrongful convictions are a recognized by-product of the criminal justice system. Further, specific policy choices can influence the number of wrongful convictions.

Most of what we know about wrongful convictions derives from the U.S.A. A wide variety of factors can lead an innocent person to be convicted, including: eyewitness identification, false confessions, Mr. Big stings, guilty pleas, systemic discrimination, forensic errors, jailhouse informants, prosecutorial misconduct, and tunnel vision by police, prosecutors, and defence counsel.

One significant issue is the pressure placed on many defendants to plead guilty before trial. The people Innocence Canada represent, those convicted of homicide, generally have not had the luxury of trial where the evidence against them was tested and heard. In 90% of criminal cases, people find it is easier just to plead out. Eyewitness identification also poses challenges. The Innocence Project estimates that roughly 70% of wrongful convictions are partially attributable to eyewitness identification error.

Finally, the same system that leads to the disproportionate mass-incarceration of racialized and Indigenous accused appears to also decrease their willingness or ability to seek exoneration. “[W]hen you look at the exonerees that Innocence Canada has had, the vast majority, quite frankly, are white men, and that doesn’t necessarily represent the populace that’s currently incarcerated,” Bhavan says. “I highly doubt [the] reason is that these individuals haven’t been wrongfully convicted.”

Failures of Policy and Recommendations for Reform

As I had hoped, Bhavan had a lot to share regarding how the Canadian legal system can improve in combating wrongful convictions. She specifically highlighted Mr. Big Operations, false confessions, jailhouse testimony, eyewitness identification, and the unreliability of forensic evidence as barrier to justice and drivers of wrongful convictions.

Mr. Big Operations

A particularly Canadian cause of wrongful conviction is the Mr. Big operation.

A Mr. Big operation generally consists of police constructing a false criminal enterprise in which the accused is persuaded to discuss elements of their alleged criminal history with a fictional criminal kingpin in order to become accepted into their fictitious criminal organization. These operations are understandably controversial given the incentives in place for an accused to embellish or fabricate elements of their criminal history, prejudice, and police misconduct born from inducing someone to speak freely on false pretenses. In R v Hart, the Supreme Court noted that these “confessions” are often extracted amid an “aura” of violence and inducements.

Bhavan explained that Mr. Big stings are a “recipe” for false confessions and wrongful convictions because police have “tunnel vision” in attempting to extract a false confession. Mr. Big operations are often used in homicide cold cases where the police have a specific suspect they want to accuse but lack the evidence to convict. As result, the police concoct a fictitious criminal conspiracy with the sole purpose of ensuring one suspect will confess. In Bhavan’s view, barring supporting evidence substantiating the testimony acquired in these stings, are not reliable enough to be admissible in court.

I asked whether the Supreme Court’s decision in Hart goes far enough in limiting Mr. Big stings as evidence. The Hart court held that barring indicators of reliability (such as specificity, use of non-publicly known information, and confirmatory evidence), Mr. Big confessions are presumptively inadmissible. Bhavan believes the Hart ruling is fair, but she is disappointed that few trial courts use the Hart standard to exclude Mr. Big statements, even when there is no confirmatory evidence available.

False Confessions

Bhavan also offered opinions on the cases of the so-called “interrogation trilogy.” In the “trilogy” cases the Supreme Court outlined basic acceptable parameters for police in interrogations.

In the first case, Oickle, the Court described how the voluntariness of confessions is assessed, including whether police trickery would “shock the community.” In the second, Singh — in which the accused asserted their right to silence eighteen times but confessed after the police refused to halt the interrogation — the Court rejected the idea that the right to silence could halt police questioning. Finally, in Sinclair, the Court found that that suspects do not have a right to counsel in the interrogation room, and held they are only guaranteed a right to re-consult with them when there has been a change in circumstances.

Bhavan’s main concern with the case law on voluntariness is whether it is adequately tailored to the vulnerabilities of the person being interrogated. Confessions are highly persuasive evidence to a jury, so it is vital they be voluntary and true. Those with mental health vulnerabilities or from marginalized communities often are more susceptible to police pressure. Bhavan also worries that police may have too much leeway to present false evidence to the accused. “There is a fine line between eliciting and inducing a confession.”

I asked Bhavan if she believes the Court made a mistake in Sinclair and Singh by not pursuing a more Miranda-style rights framework, with counsel in the room and limited rights for an accused to pause interrogations. Bhavan says she understands why police prefer our system. However, she has worries when interrogations become an endurance contest between a suspect and police, when an accused may not know all their rights, and when they do not have access to their lawyer unless the circumstances change. “[F]or me, it’s worrisome because the voluntariness is highly questionable in those circumstances,” Bhavan says.

Jailhouse Testimony

Jailhouse informants have been a source of over a hundred wrongful convictions in the United States. I asked Bhavan if the Canadian situation was comparable. She said that while Canada unfortunately still uses jailhouse testimonies, it uses it far less than the U.S.

“[T]his is testimony that cannot be trusted,” Bhavan explains. “Time and time again, in many wrongful conviction cases, we’ve seen how susceptible juries are to the evidence of a jailhouse informant. We’ve seen that it has been a cause of wrongful conviction and we’ve seen that this evidence can’t be trusted.” Accordingly, Bhavan believes that nothing short of a presumptive ban on admissibility would be sufficient. “I think that we really need to take a very strong stance on this type of evidence.”

Eyewitness Identification

Following up on the ubiquity of false eyewitness identification in wrongful convictions, I asked Bhavan if she sees a jurisprudential or policy-driven route out of the problem, or whether human error will always be a concern. Bhavan suggested there are some systemic ways to reduce the problem.

Eyewitness testimony — someone saying “I saw who did, they are here in the courtroom, and they are over there” — will always be seen by a jury as strong evidence. However, the court can mitigatea jury’s willingness to jump the gun if they give judicial notice to some of the literature of eyewitness frailties, or if they allow expert evidence to opine on the dangers of giving such testimony too much weight. Bhavan is glad to see increased recognition of this issue in Canada and Ontario and that the frailties of eyewitness testimony are now more frequently mentioned in jury charges. The next step is to have experts offer evidence on eyewitness testimony. Bhavan believes that while a court “might see it as redundant,” it really would be valuable.

“[T]here’s something to be said where you have an eyewitness that is before the court in person, and then also at the same time, there’s someone who will be able to, not necessarily refute, but also to kind of flag the evidence with another person who has an expertise in that particular area,” Bhavan explains.

Forensic Science

With respect to forensic science, Bhavan was clear that criminal lawyers need to know more. We may not be doctors, but we have a duty to understand, scrutinize, and question scientific information put before the court.

We know bad forensic science is an important cause of wrongful convictions. Moreover, even if the Crown is using well regarded methods such as DNA evidence, there are still failure points. Wrongful convictions have occurred because of DNA forensics done improperly. Despite the lure of scientific objectivity, it is always important to scrutinize the evidence as part of a human system. Counsel and the trier of fact need to think about forensics in relation to other evidence, not to see it as the evidence. If things do not add up, that needs to be considered and questioned.

The Importance of Innocence Canada’s Work

I came to Bhavan seeking insight into the systemic failures that cause wrongful convictions, but I would be remiss if I did not address one factor that allows them to persist: our failure to adequately support the groups that fight them. At the end of the day, Innocence Canada is a non-profit organization. The lawyers who work there depend heavily on a team of volunteer counsel and case-reviewers, and they could not operate without public funding, which has at times been short on supply. Although they currently focus primarily on homicide convictions for triaging reasons, Bhavan says there are strong reasons to believe wrongful convictions may be more common for lesser offences. If Innocence Canada ever has the capacity to expand its case roster, the cause of justice in both Ontario and Canada would be greatly advanced. As it stands, it is important that the public and legal community not only continue to support, but expand our support, of the vital work Innocence Canada does.

Editor’s Note: this is an abridged version, read the full article on the CLSA’s website.

This series by the Criminal Law Students’ Association introduces the law student body to the wild, wild world of criminal law and criminal justice. Articles will be published in print in Ultra Vires as well as on the CLSA’s website, uoftlawclsa.weebly.com/blog. To pitch an article to the CLSA blog series, please contact the CLSA Blog Editor, Teodora Pasca, at [email protected].