A conversation about anti-Asian racism, whorephobia, and policing in Canada

Elene Lam is the Executive Director of Butterfly, the Asian and Migrant Sex Workers Support Network, and a PhD candidate at McMaster University’s School of Social Work. She has been advocating for sex worker, migrant, labour, and gender justice for over 20 years. Butterfly is organized by and supports workers in holistic centres, body rub parlours, and the sex industry in Toronto.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Sabrina Sukhedo (SS): The heartbreaking killings in Atlanta represent a horrific rise in anti-Asian violence during the pandemic. How has this violence impacted the Asian and migrant sex worker community in Toronto?

Elene Lam (EL): We feel very sad and heartbroken. But at the same time, we know that this is not a faraway problem. This also happens in Canada. We have workers in Hamilton, Toronto, and Mississauga who are being murdered. This is not new. This is something experienced by the community everyday.

While the violence issue is a huge concern within the community, the problem is actually policing and repressive laws, which make workers unable to protect themselves.

For example, at the city level, there is excessive investigation of massage parlours and a lot of ticketing. When massage parlour workers tried to lock their doors, they were charged. The City of Toronto has said that they are no longer enforcing the bylaw [that prohibits locked body rub rooms in parlours] after the murder [of Ashley Noell Arzaga last year], but these policies still exist. These bylaws make workers unsafe.

On one hand, we think that all this public concern about anti-Asian racism is good. But we are worried that people will forget that this is not just racist violence. This is also violence as a reuslt of anti-sex work sentiment, “whorephobia,” and moralistic views about sex and sexuality. We hope that people remember that there were other people in the massage parlour who were murdered. Whether they do sex work or not, people are being harmed by sex work laws and discrimination against sex workers because of their association with sex workers.

SS: Butterfly has raised concerns that anti-trafficking groups will exploit the Atlanta tragedy. How do these groups cause harm to Asian and migrant sex workers?

EL: So often we see anti-sex work and anti-trafficking organizations use the safety issue to advocate for more repressive laws and law enforcement against sex workers. Many anti-trafficking organizations — particularly religious and Evangelical groups — are actually anti-sex work organizations. They conflate sex work and trafficking. But because they use the language of anti-trafficking, people don’t see that.

Many people say anti-trafficking groups are radical feminists or feminist organizations, but I don’t call them feminists because they support the police more than they support women. And we know very well that policing does not make workers safe. Policing and criminalization actually puts them in danger.

We are extremely worried that these organizations will use this opportunity and racist ideas about Asian women being trafficking victims who don’t want to do sex work to advocate for more harmful policies, including more policing in massage parlours, shutting down the businesses, and increasing police powers to investigate sex work in hotels and apartments.

SS: What sort of policies and legislation enacted by the government contribute to the marginalization and vulnerability of Asian and migrant sex workers?

EL: One of the policy issues I want to raise is the Ontario government allocating more than $300 million to anti-trafficking groups and proposing changes to anti-trafficking legislation [through Bill 251, the Combatting Human Trafficking Act].

We are surprised that there are so many people concerned about policing, police powers, and racial profiling, yet so many groups — including organizations dedicated to human rights work and ending gender-based violence — still support policing in service of anti-trafficking work. They support increased powers for police to conduct investigations and for Children’s Aid Society (CAS) to control youth. We know how harmful, historically, CAS has been to racialized youths in particular.

This new anti-trafficking bill requires hotels and other accommodation businesses to record personal information of anyone using their rooms and empowers police to access that data without warrants. This bill also increases police power to investigate, so police can enter any space, or carry out any investigation, without court orders. We know from the pandemic that when police have the power to access data, they abuse the system.

Furthermore, we don’t see any human rights organizations speaking loudly against this bill because they are afraid that they will support the trafficker. That gives so much power to the state and government to promote these harmful policies.

Anti-trafficking policies are a cover for racism and racial profiling. They assume that Asian women are victims who need to be rescued. And it won’t be rich, white people who will be checked in at a hotel. Of course, it will be racialized communities. They use anti-trafficking work to justify their racial profiling and surveillance. We have so many workers being arrested and deported, so increasing police powers just further pushes workers underground and increases the risk of harm. This is why it’s necessary to take immediate action around this issue.

SS: Because of the criminalization of sex work, migrant sex workers have often assumed the responsibility of protecting each other. How have migrant sex workers and Butterfly organized to address the increased harms to their community?

EL: Butterfly is a grassroots organization that organizes workers to speak out. In 2019, 300 workers were at City Hall speaking out. They said that they were not trafficking victims, they need the work. They demanded the City to stop shutting down the massage parlours and taking away their businesses. Their safety is the concern, so they are still organizing and advocating. As a result, the City is now willing to not enforce the law around door-locking.

But this is a tiny step. Workers are still being policed, racially profiled, and criminalized. So, workers in massage parlours and the sex industry are reaching out to different community members and educating them. These workers are also collecting voices and evidence around how this is harmful to them. We are also building allyship so that the community has the power to bring about the necessary change.

SS: These women’s lives sit at the intersection of racism, misogyny, and classism. How does examining this intersection inform your advocacy?

EL: Intersectionality is so important. We hear many Asian groups — particularly the more privileged in the Asian community — say that they want more police to address hate crimes. Intersectionality tells us that these issues are not only about race, but also class, immigration background, and occupation. These experiences make a huge difference.

We also recognize how this dynamic plays out in the political arena. When we lobby at City Hall, we have 300 workers there, but we are not as powerful as one white, privileged woman from an NGO saying, “There are a lot of Asian women being trafficked, we need to change the law and kill the sex industry to make them safe.” We see this power imbalance, so having workers speak out is important but not enough. We also need to build allyship.

As law students, we really hope that you look at trafficking issues through a critical lens. Doing anti-trafficking work looks fancy and cool and attracts a lot of money, but the work is also often anti-migrant, racist, and whorephobic. Anti-trafficking policies harm migrants, increase the policing of Black, Indigenous, and Asian communities, and criminalize sex work. Building allyship with the labour movement, human rights organizations, and organizations fighting gender-based violence is important to us.

SS: What legal reforms are urgently needed to keep Asian and migrant sex workers safe?

EL: We keep telling the public that policing is not the solution. Workers are unsafe because of the police. But the reason police have all the power, and workers are put in danger, is because of problematic laws and policies.

When two people work together around sexual services, they are criminalized. When someone helps to screen clients, or advertise a worker’s sexual services, they are criminalized. These important protective measures are all criminalized.

There are also harmful immigration laws. Any worker in the sex industry who is not a permanent resident or citizen can be removed from Canada. There are also several repressive city bylaws against massage parlours.

We know how these laws are harmful. Workers are organizing and telling the public how these laws are harmful, and how they want them to change.

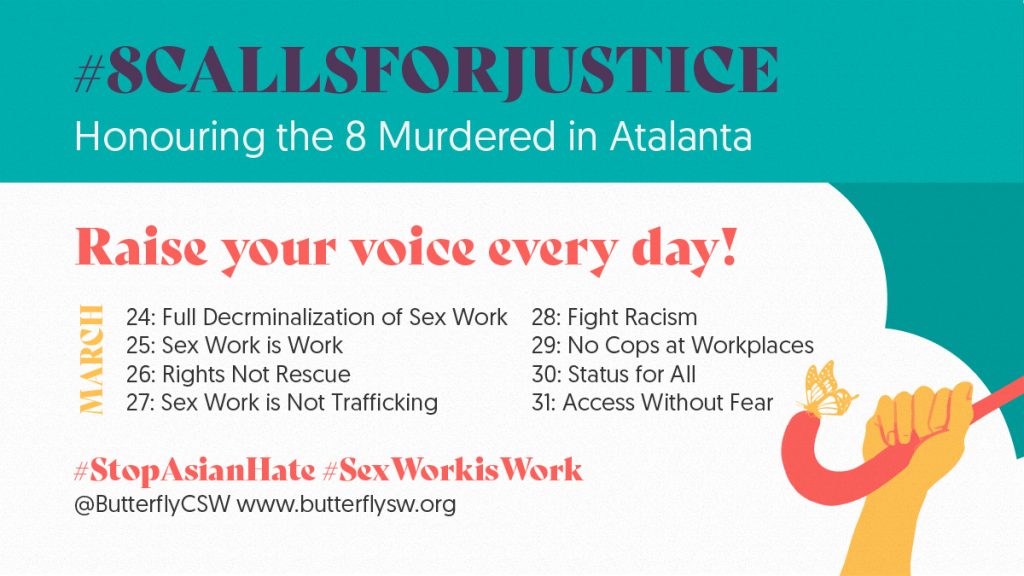

Visit https://www.butterflysw.org/8callsforjustice to learn about Butterfly’s 8 Calls for Justice campaign and to sign their declaration of support.

A version of this article appears on Rights Review’s website here.