A compelling tale of two communities, one on each side of Manitoba’s Birdtail River, living drastically different lives

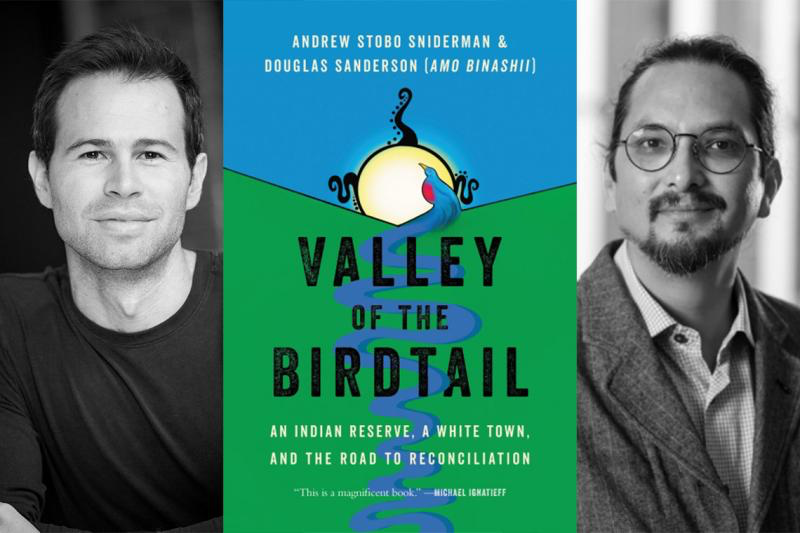

Often, the best way to illustrate patterns of difference, particularly as it relates to State policy, is through direct comparison. In their new book, Valley of the Birdtail: An Indian Reserve, a White Town, and the Road to Reconciliation, Andrew Stobo Sniderman and the Faculty’s own Professor Douglas Sanderson (Amo Binashii) seek to do just that.

Part narrative storytelling, part historical review, Valley of the Birdtail endeavours to highlight, critique, and explain the well-documented divide in outcomes between First Nations communities living on reserve and the broader Canadian population. This book follows the lives of two families living across the Birdtail River in Manitoba—Troy Luhowy and his father, Nelson: generational Ukrainian immigrants living in the settler town of Rossburn; and Maureen Twovoice, her mother, Linda, and her grandfather, Michael: Anishinaabeg living on the Waywayseecappo First Nation (Wayway) reserve.

Despite their close geographical distance, the communities of Rossburn and Waywayseecappo could not be further apart when it comes to educational opportunities. The book highlights the lack of equal educational opportunities between students of Rossburn and Indigenous youth living in the community of Wayway. While students in Rossburn attend their provincially funded Rossburn Elementary with ease, Wayway youth have been denied the opportunity of safe, effective, appropriate, and well-funded education for generations.

The children of Wayway were removed from their families and enrolled in residential schools hundreds of kilometres away, where they learned more about pain and religion than math and science. Following the end of the residential school regime, in an attempt to improve outcomes, First Nations students were enrolled in the Rossburn local school—where settler students and teachers, having never properly interacted with their Wayway neighbours, tormented their classmates with racist bullying, stereotyping, and mistreatment—or were subsequently educated at a school on the reserve, where funding was $3,000 less per student than Rossburn, a deficit of a million dollars a year.

Valley of the Birdtail takes a deep dive into this reality, explaining the long history of policy and law that permitted such disparate educational systems and contextualizing it with the experiences of the students educated in each era. Through the story, readers begin to understand this separation in treatment as one component of a centuries-long history of racism, denigration, paternalism, and neglect from the agents of the Crown towards the first inhabitants of what is now Canada.

Valley of the Birdtail also explores the lives and decisions of important historical actors in the Birdtail region. From those with complex records, such as Clifford Sifton (the man responsible for championing residential schools and for inviting hundreds of thousands of poverty-stricken Ukrainians to homestead in Canada for free) to outright villains, like Hayter Reed (a man who simultaneously sought to outlaw traditional dancing on reserves while performing bastardized native dances himself at Parliamentary parties, complete with seized traditional clothing and smudged red face paint), Sniderman and Sanderson take the reader on an expansive journey to illustrate the power held by the Department of Indian Affairs and its agents, from the reserve pass system, to the denial of agricultural technology, to regimes of forced starvation.

Valley of the Birdtail contrasts this treatment of Indigenous communities with the history of Ukrainian settlement in Manitoba. At the same time as the Canadian government was forcing the First Nations onto smaller reserves, the country was granting hundred-acre plots to Ukrainian immigrants for free. While state agents were actively suppressing Indigenous dance and clothing, politicians and bureaucrats were praising the new Ukrainian traditions of dancing and costuming these immigrants brought with them. And, when existing white settlers began to display racist attitudes towards Ukrainian newcomers, local and national governments took action to stop those attitudes in their tracks and defend their newest Canadians. Such protection was not extended to Indigenous peoples.

The Valley of the Birdtail offers a glimpse into the lived disparities between two communities divided only by race and a river. This book aims to demonstrate the pervasive role that structural, systemic racism has played in the long-term outcomes of Indigenous peoples and how narrow or short-term solutions will always fail to achieve true equity. Sniderman and Sanderson end their book with several large-scale, sweeping reforms they propose will more effectively address the inequities ingrained in the current political status quo, from true Indigenous governance to transfers of jurisdiction over land. Overall, the Valley of the Birdtail is a compelling articulation of complex systems of oppression—both social and legal—that First Nations communities face, offering guidance and clarity on effective and thoughtful ways forward. It is well worth the read.