What can that tell us about our country’s treatment of Indigenous peoples?

Uluru Statement From the Heart: “This is the torment of our powerlessness.”

On October 14, 2023, Australians voted”‘no” on the Indigenous Voice to Parliament Referendum. The Referendum, which stemmed from statements of reconciliation and recognition of Indigenous peoples, was an attempt to constitutionally recognize Indigenous and Torres Strait Islander people, and to provide a “committee of Indigenous Australians, chosen by Indigenous Australians, giving advice to government so that we can get a better result for Indigenous Australians,” as simply described by Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese.

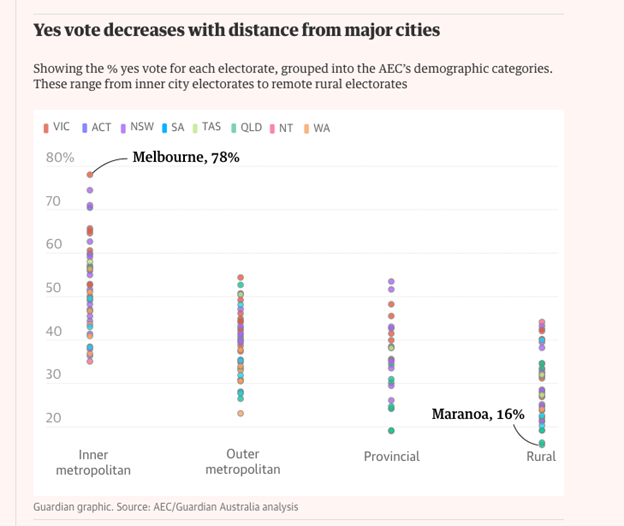

In order to pass, the referendum needed both a majority nationally and to pass in four of Australia’s six states. None of the states ended with a majority, and 60.8% of voters responded “No” to the initiative. However, in areas where the population was majority Indigenous, such as Momington Island, the “Yes” vote had high numbers. Similarly, many inner metropolitan areas had higher voting percentages of “Yes” than outer metropolitan and rural areas.

Uluru Statement From the Heart and the Voice to Parliament

The Voice to Parliament (Voice) was one of two calls stemming from the Uluru Statement From the Heart, a statement created in 2017 by 250 Aboriginal and Torres Islander people at the First Nations National Constitutional Convention. The 12-paragraph statement details the sovereignty of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples stemming from ancestral connections to the land of Australia for over 60,000 years. It further describes the systemic discrimination and disparities faced by Indigenous Australians:

We are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people. Our children are alienated from their families at unprecedented rates. This cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. They should be our hope for the future. These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is the torment of our powerlessness.

The statement thus calls for constitutional reform to empower Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people through the Voice initiative and for the establishment of a Makarrata Commission, a supervisory body for agreement-making and truth-telling.

The Voice was ultimately a simple, middle ground that would give Indigenous Australians the opportunity to speak on issues that impact them. In this way, it is not unlike business councils and mining groups, which already have representation through advisory bodies when legislation could impact the people they represent. As for inclusion in the constitution, Australia would be following the recognition of Indigenous peoples in the Canadian constitution in 1982 (see s.35 of the Constitution Act) and New Zealand’s treaties with the Maori peoples in 1840.

“If you don’t know, vote no.”

The mechanisms by which the “No” vote gained traction follow a disturbing trend in voter apathy rationalized through universalizing anti-division arguments. Over-arching the vote’s entirety were the power dynamics present in the systemic discrimination of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

There were two simple slogans used by supporters of the “No”’ vote: “If you don’t know, vote no” and “One together, not two divided. Vote No to the Voice of Division.” The anti-education stance on voting plays to the overall avoidance tactic used by dominant societies to disengage with the discussions around movements towards equality. This avoidance is marked by denial of the realities of colonialism. In an open letter from over 70 constitutional and public law teachers, they note that “it is wrong to frame the Voice as introducing a racial divide into the constitution… the racial divide has always been there.”

The messages of racial divide are arguably a distraction to the real fears that voters acted upon—that providing an Indigenous voice to Parliament would damage the rights of other Australians, particularly land rights. This is a similar argument to what we see frequently in Canada, especially in questions of private landholders versus title claims. This false dichotomy and belief of scarcity of rights is frequently utilized in colonial nations to deny the rights and self-determination of Indigenous populations. Dean Parkin, who led the campaign in support of the referendum, addressed this concept directly after the vote was called: “I want to speak very directly to those Australians who voted no with hardness in your hearts. Please understand that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have never wanted to take anything from you. We have never and will never mean you no [sic] harm.”

Apathy as an Excuse for Discriminatory Practice

As colonial nations, both Australia and Canada have to grapple with motions towards reconciliation with Indigenous people and address the vast systemic inequalities plaguing our societies. Such reconciliation can never be accomplished through willful blindness to the realities of colonial damage or the continuous denial of self-determination of Indigenous people, even if these denials are covered with innocuous ideologies of avoiding discord and division. As our nations continue our reconciliatory processes, non-Indigenous persons must engage with, learn about, and truly listen to the voices of Indigenous people. There is no excuse for not knowing.