Bilal Manji (3L) and Dave Marshall (4L)

The verdict is in: 2015 was not a fluke. Just one year after the most successful year in the history of competitive mooting at U of T Law, another talented cadre of mooters has done it again. Seven first place finishes, six top oralists, five top factums, five second place finishes, eight oralist awards, and two factum prizes have been added to the Faculty’s collective resumé, and the repeated embarrassment of riches suggests that the various parts of U of T’s mooting machine are doing something right.

We are extremely proud of our mooters. It was only after allowing the victories to sink in—and more than a gratuitous number of high-fives and back-slaps—that we began to turn our minds back to the question that has preoccupied the Moot Court Committee (MCC) all year: how can the competitive mooting program be made accessible to as many students as possible?

In a similar tradition to the MCC members who came before us, our goal is to highlight a few challenges with mooting at U of T in the hope that we can continue to grow what is already, by all accounts, a successful program. Our concerns fall into four categories: (1) equity in selection; (2) the role of student coaches; (3) faculty involvement; and (4) the number of mooting opportunities.

1. Equity In Selection

In the current selection process, students are evaluated on their performance in two try-out rounds. After registering for a try-out, students are e-mailed problem materials that include: facta from both sides of a fictitious case, two relevant SCC decisions, and a “Mooting Tip Sheet.” Students are also invited to attend an MCC-hosted information session in which past mooters discuss their experiences, and the MCC provides suggestions on try-out preparation.

In September 2015, 103 upper-year students participated in a first-round try-out and 82 progressed to a second-round try-out for one of 58 total competitive mooting spots.

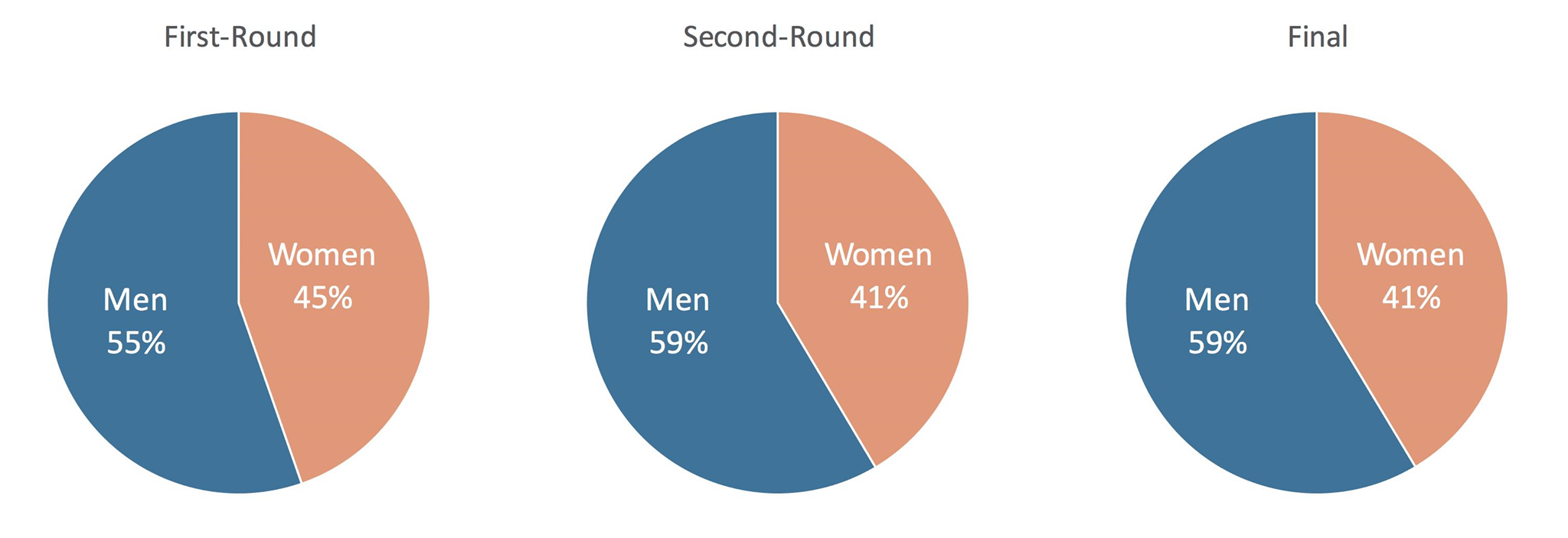

As part of the MCC’s efforts to increase the accessibility of mooting, we monitored the demographics of the tryout participants. Notably, we found that men were slightly overrepresented in the tryout process. Despite efforts by the MCC to ensure gender-balanced judging panels, the ratio worsened slightly between try-out rounds and between the first round and final team selection. We encourage next year’s MCC to continue to measure these statistics—on both gender and other lines, using self-reported statistics—to ensure that the try-out process is equitable.

Recommendation: The MCC should continue to evaluate the reasons why students self-select out of the try-out process. This analysis must go beyond gender boundaries to reach students who are visible minorities and in other historically underrepresented groups, as well as students who may be self-selecting out of participation on other bases, such as the lack of high-school debating experience. Interventions to address the latter of those issues may also come in the form of exposing students to mooting earlier on in their legal careers, perhaps by encouraging more first-year mooting programs to accompany the Baby Gale, or by adding a mooting requirement to the first-year LRW class.

2. The Role Of Student Coaches

Student coaches are the unsung heroes of the competitive mooting program. Student coaches review factum drafts, arrange and judge run-throughs, coordinate factum reviews and run-throughs with practitioner coaches and Faculty members, and attend local moots. It was incredible to see the coaches’ dedication to their teams. These students’ contributions to the mooting program come at personal cost, one that we do not adequately compensate.

Student coaches are presently offered one ungraded credit if they write a paper on the substantive legal issues of the moot that they coached. Coaching is a valuable pedagogical experience. It requires that coaches become intimately familiar with the substance of their team’s submissions. We believe the paper requirement, at least in its current form, is not the most appropriate, nor least onerous, way of evaluating the knowledge amassed by student coaches.

Recommendation: Student coaches should receive one ungraded credit if they edit a minimum number of factum drafts and judge a minimum number of run-throughs. This form of evaluation would require greater supervision by faculty advisors assigned to each moot, but that might bring about the positive side-effect of increasing faculty involvement in mooting.

3. Faculty Involvement

Our professors are leaders in their respective fields, and many of them enthusiastically contribute their expertise to various mooting teams. Many are also fierce advocates for U of T’s mooting program. Yet a perpetual complaint from mooters is that the faculty should be contributing more to the mooting program.

This is a complicated issue. Some professors would like to contribute time to moots, but cannot conduct factum reviews on a short turn-around basis. Others wish to contribute, but do not feel particularly well-suited to conducting oral run-throughs. Both of these practical concerns are underpinned by a now quieted, yet persistent, opinion amongst some faculty members that mooting has less pedagogical value than traditional classes.

Our year serving on the MCC and as student coaches has illustrated to us the importance of making efforts to get the faculty meaningfully “on board.” Student coaches are incredibly valuable, but like practitioner coaches, their role is inherently limited. We are not experts at law, and we are coaching our peers. Faculty members have a unique role to play in helping to guide mooters’ research and reasoning.

Recommendation: Faculty Council should set minimum requirements for moots’ assigned Faculty coaches and for Faculty members more broadly. Faculty coaches should be encouraged to participate early and often in competitive moots, in particular by helping to set teams off in the right direction as mooters begin to embark upon their respective research problems, and by helping to edit factum drafts if appropriate.

4. The Number Of Mooting Opportunities

Competitive mooting is in demand at U of T Law. Just ask the “keen” first-year cohort that nearly broke the Internet by signing up for all 70 available First-Year Trial Advocacy spots (and half of the waitlist) in 46 seconds. There are 58-60 competitive mooting opportunities per year, which unfortunately means that many capable mooters are being turned away. If more moots were available, a greater number of students would be able to benefit from this unique pedagogical and team-building experience each year. Greater variety in subject matter across moots would also enable a greater number of students to develop their skills in an area of law in which they have interest.

Recommendation: The Mooting and Advocacy Committee—the Faculty Council committee responsible for approving new moots—should consider competing in more competitive moots, including the prestigious Willem C. Vis International Commercial Arbitration Moot.

Conclusion

Our success in this year’s competitive moots, and the level of interest in First-Year Trial Advocacy and the Baby Gale, demonstrates that the future of oral advocacy at U of T Law is clearly very bright. Yet, as always, improvements can be made. Faculty, students and the administration are partners in whatever changes must be made, and we are pleased about the small improvements—and the big discussions—that we have been able to start this year.

We have had the privilege of serving on this year’s MCC—along with Rachel Charney, Sam Greene, and Brett Hughes—and we wish the next MCC—Simon Cameron, Stefan Case, Veenu Goswami, Victoria Hale, and Shane Thomas—all the best in spearheading these efforts and continuing the success of the competitive mooting program next year. We also encourage all students to weigh in on the conversation—this is our program, and it is one that we must continue to work together to improve.