How my hunt for the perfect Halloween costume turned into an exploration of obsession, ethics, and international law

Disclaimer: The author does not intend any of the legal commentary included in this article to be understood as legal advice.

The Obsession

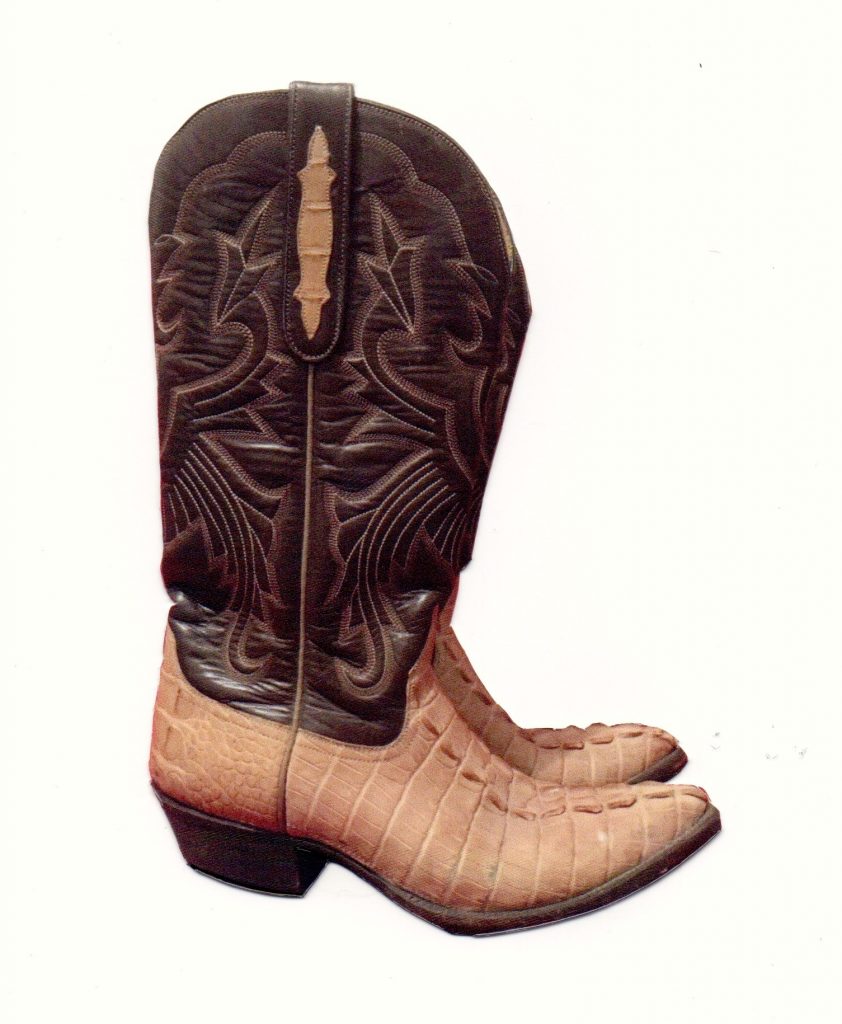

This is a $5,000 pair of boots. I bought them for $90. But I almost sold my soul to pay the bill.

Bargain hunting is my drug of choice. I crave the endorphin rush of deep discounts. Ninety percent off kind of discounts. I spend about an hour each day prowling the digital savannah, stalking sales with unwavering focus.

Clothes are my favourite thing to shop for: they fulfil my need to express myself while serving a practical purpose. I do not buy much, but I buy quality. My clothes feel better and last longer. I still have a pair of raw denim jeans from 2005 and a cashmere sweater from the nineties, when Burberry was called Burberry’s. But the end result is incidental—I really just love the thrill of finding something special.

Bargain hunting serves another purpose: it is a fantastic distraction. To make really advantageous deals, you need to commit yourself fully. You need to know what a good deal looks like and where it is likely to hide; you need to know your prey. This takes time and dedication—time and dedication that might, I admit, be better placed elsewhere.

I have had mixed feelings about law since I arrived here two years ago. I enjoy law, but it was never really one of my interests. Nor has it proven to be one of my strengths, even when I really try. I am a middling law student at best. As such, there are not many accolades to strive for. I did well at my job, because I pride myself on hard work, but now, with a job in hand, I find it difficult to stay motivated in school. These days, I welcome distractions like gallery visits, elaborate meals, and, yes, online shopping.

Until a few weeks ago, my pastime had an air of plausible deniability to it. I could tell myself with slightly feigned conviction that it was just something that I did at tea-time—a ten-minute escape from the drier topics of legal study.

Then, I found these boots. My girlfriend and I had been brainstorming Halloween costumes. She suggested that we do something western: SExSW (Sex by South West). I loved it. I spent the first years of my childhood in Cochrane, Alberta, idolizing cowboy masculinity. Dressing up like an extra for The Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada sounded like the perfect excuse to live a real-life fantasy of mine.

I started researching cowboy boots: a nice pair was the only missing element of my costume. I quickly learned that an El Paso company called Stallion makes the finest ones money can buy. They start at USD $1,000. I was looking for part of a Halloween costume—something that most people get at the Dollar Store. But I was really looking for a serious addition to my wardrobe that I could also wear as part of my costume. I looked on eBay and immediately found what, in monetary terms, was the best deal I have ever come across: the pair of Stallions reproduced here.

Photo credit: Tom Collins (3L)

The Law of Nations

There was just one problem. The lower part of the boots was alligator leather. American alligator is a protected species under Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). Trading in endangered species is ethically fraught and, with good reason, a heavily regulated activity. CITES sets out the guiding principles for signatory countries’ trade regulations. The convention covers more than 35,000 species of plants and animals and groups them into one of three appendices according to vulnerability. Appendix II, which includes the American alligator, covers species that are not necessarily threatened with extinction, but which may become so unless trade in them is strictly controlled.

Signatory countries to CITES fulfil their obligations in different ways, with tailored import and export permits being a central means. Navigating the panoply of licenses and permits is challenging—I suspect deliberately so. My current understanding is that, to import alligator skin boots into Canada through a commercial contract, one needs two things: an export license and a specific CITES-compliant export permit. The US Fish & Wildlife Service is responsible for issuing both documents. To get a license, it looks like you need to pay the USFWS USD $100 and retain a US-based record keeper for five years. To get a permit, you need to be able to prove the exact provenance of the alligator skin. I could not do either of these things.

There are legal ways to circumvent the above requirements: you can show that you inherited the alligator product. You can also show that the alligator product dates from before the treaty (i.e. before 1973). Neither of these exceptions applied to me. You can, however, just wear the alligator product across the border. That’s right. All I had to do was take a bus down to Niagara Falls, witness the majestic splendour of the waterfall from the US side, visit a nearby warehouse, put the boots on my feet, fill out a special customs declaration and walk back across the border. It was so simple! Besides, what’s another $100 and a day trip to one of the Wonders of the World?

Although I meant that question rhetorically, when I heard myself ask it, I started to wonder if I had begun to lose my mind. I ultimately concluded that I had, but only partially because I was contemplating an international jaunt to secure part of a Halloween costume.

The Ethics

One evening, I was speaking to my mum. She has been a lifelong advocate of animal rights and animal welfare. I owe the majority of my most compassionate values to her teaching. She thought that it was absurd that I was contemplating travelling to the US just to buy a pair of boots; however, her main objection was that the boots were alligator skin. My mum urged me to consider whether I really wanted to advertise that it is acceptable to wear exotic animal skins. She reminded me that I unequivocally opposed to wearing any fur, however obtained, because I believe that it causes needless animal suffering. She believed that these boots were no different.

Initially, I was not convinced. My resistance flowed not from a belief that alligator skin boots were fundamentally different than a fur coat, but from a logical conflict: I wear cow leather. Don’t cows suffer needlessly? I had tested what seemed like an arbitrary principle and concluded that it was arbitrary. The question was whether this principle was also morally misplaced.

My mum offered two other justifications for her stance. First, she argued that because cows are killed on a much larger scale, there is more oversight for their well being than for alligators. I was not convinced. The meat and leather industries are horrific, regardless of whatever oversight there is supposed to be. Second, she argued that, at least, people will eat the cow’s meat; few people eat alligator. Again, I was not convinced. If the argument is about net waste, then it is probably safe to say that far more cow products are wasted than alligator products (if only because there is less production of the latter). On the other hand, if the implication is about unit waste, then the argument fails to contemplate the possibility that most cowhides do not become leather goods.

I was in conflict. I wanted to hang my straw hat on a principled rejection of unnecessary cruelty. Yet, I was still enchanted by the lure of potential savings. I was prepared to admit my human contradictions. I asked, “if everything I do, as a person, causes pain, do any of my actions matter?” Yes, my mum assured me. We have a choice, as individuals, to resign ourselves to the apathy of complacency and the cynicism of complicity or to strive to do better: to try to minimize the suffering that we cause. She was right, of course.

Ultimately, I let them go. The boots had run into problems at customs, anyway, because the seller never bothered to get the proper CITES permit. I got my money back; the seller got his boots back. I took the opportunity to regain some perspective and control. I am still going as a cowboy and I am still wearing some flashy boots, just not ones that require such a spectacular feat of legal and ethical acrobatics.